This post is also available in:

Following the presence of cracks in the Rana Plaza building, home to a bank and numerous shops located on the first floors of the building, operators were advised not to return the following day. This information was deliberately revisited by the owners of the textile factories in regards to the workers of the upper floors, who kept returning to work every next day, unaware of what was about to happen.

Several factories, some irregular, some not. The one certain thing is that the structure of Rana Plaza, owned by Sohel Rana, a prominent member of the political party of the Bengalese People’s League, was not prepared to house factories as the building was not was built to support the weight and vibrations of heavy textile machinery, mostly because of the 3 abusive plans that had been added to the initial 5 floors.

April 23, 2013, 08:45 am The Rana Plaza collapses: 1138 dead textile workers, 2515 wounded workers extracted alive from the rubble, some of which then contributed in the search for survivors: men, women and children. Children employed as workers and children left to the internal corporate nest.

That of the Rana Plaza will be remembered as the greatest accidental structural failure of human history, as well as the greatest fatal accident in a textile factory.

Some brands of clothing for which these factories produced are Auchan, Primark, Sears, Walmart, El Corte Ingles, Benetton, just to name a few.

And before the Rana Plaza there were many others: 2012 Tazreen Fashion, in Ashulia another sub-district of Dakha, a short circuit next to a synthetic fiber yarn engages a fire, 117 dead and over 200 injured; 2012, Alì Enterprises, Karachi, Pakistan: a fire causes 254 dead and 55 injured. We could go on for pages in the long series of exploitative obituaries and we could go on uninterruptedly in this sad chronology. Certainly, among insurrections, demonstrations and protests, other 18 garment factories were closed in the following months, Sohel Rana was arrested along with the owners of the factories and they all ended up paying a 6-month security as well as new security measures, which were first predisposed, then revised and finally lightened.

On June 5 2013, the police opened fire on hundreds of former workers and relatives of the victims of the collapse, protesting for arrears, compensation promised by the government and a salary increase compared to the 38 $ per month for which the 1138 people worked in conditions of slavery losing life.

$ 38 monthly: Slavery to the current world.

Since the collapse of the Rana Plaza numerous campaigns have been activated to sensitize the production and conscious purchase among them the Fashion Revolution. This Revolution has distinguished itself for being the global non-profit movement that has been able to involve, and still involves, thousands of people in the world that answer the question: “Who made my clothes?”.

The Fashion Revolution has designated the disaster of Rana Plaza’sanniversary, whose media resonance has been such as to give the necessary breakthrough to the textile industry by promoting fashion in an ethical manner and in respect of the people and the environment. Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro, co-founders of the movement and for over 20 years engaged in the British fashion industry, said that until everything in the fashion industry will be focused on profit; human rights, the environment and workers’ rights will be destined to have a marginal role that will lead not only to suffering and hunger, but also to death. Fashion Revolution is committed to building a future in which accidents like this will never happen again. Knowing who makes our clothes is the first step in transforming the fashion industry that requires transparency, openness, honesty, communication and responsibility. Reconnecting broken links and celebrating the relationship between customers and the people who make our clothes, our shoes, accessories and jewelry. All that we call fashion.

Starting in 2016, the day of Fashion Revolution became the Week Fashion Revolution, from April 18 to 24, involving over 90 countries worldwide. This first phase of the fashion revolution began with the Fashion Question Time at the Houses of Parliament in the United Kingdom and with the launch of the first edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, which involved 40 of the world’s leading fashion companies, in light of information related to their supply chains.

In April 2016, the Fashion Revolution reached 22 million followers who answered the question “Who made my cloths?” Reiterating the hashtag: “I made your cloths!”.

Now on its fifth edition in 2018, the Fashion Revolution week took place worldwide from April 23 to 29 and according to Marina Spadafora, the Italian ambassador of the organization, “the Fashion Revolution is meant to be the first step in the awareness of what it means to buy a piece of clothing, towards a more ethical and sustainable future for the fashion industry, respecting people and the environment “.

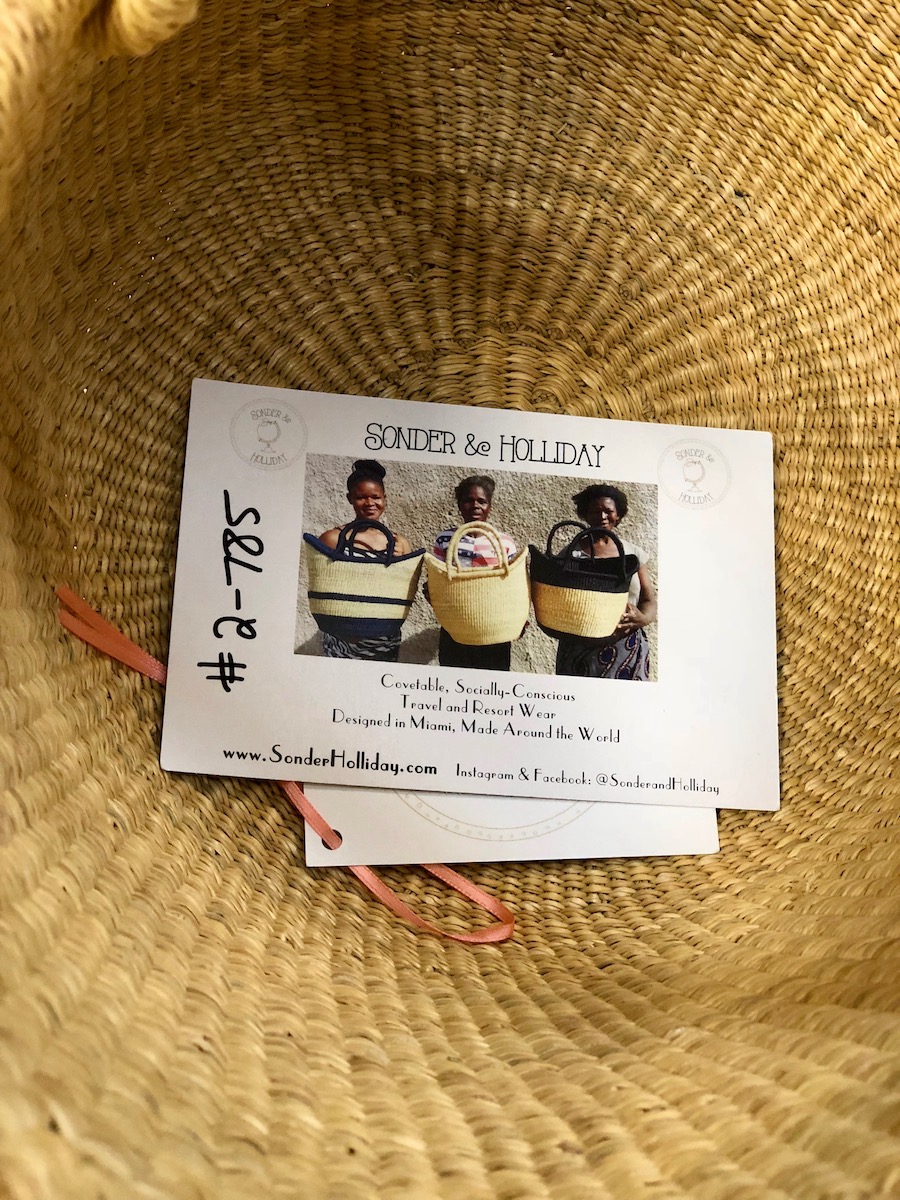

In Miami, the Fashion Revolution took place on April 28 2018 at the Sharron Lewis Design Center, organized by Nathalia Orquera blogger of “Maria Loves Green” and Colleen Coughlin of “The Full Edit”. It was sponsored by Patrick Duffy’s Global Fashion Exchange and the fashion show in Miami involved characters of the fashion world and owners of some of the most exclusive shops in the city that were born and operate in compliance with ethics, sustainability and transparency in the fashion industry. Including Sophie Zembra by Antidote, Karelle Levy by KRELwear, Veronica Pesantes of The Onikas, Caroline Colleen Coughlin by The Full Edith, Caroline K by Carolina Kleinman, Valeria Savino by The Nomad Tribe; in addition to them Francesca Belluomini, fashion blogger, writer, and author of the book “The cheat sheet of Italian Style” and the blogger Nathalia Orquera.

The day opened with a panel of discussions. Among opinions, questions and answers, emerged problems related not only to the conditions in which handcrafters live in, that resemble slavery, but also to the need for a supply chain control and the use of eco-sustainable materials along with the need to give solutions and answers to waste disposal in the textile sector. Above all the low-fashion with its vital and distorted dynamics makes the speed of reassortment one of the fundamental keys leading to success. In the last 15 years the increase of income at global level and the spread of a “fast” fashion which offers lower prices, with a number of collections equal to 10/12 a year, provides the trends of the moment at a really fast time.

As far as it concerns the retail sale, the wide availability of clothing items that are always different in style and with affordable costs, leads to the serial purchase and the accumulation of clothes in wardrobes with the risk of congesting their disposal and then end up in the garbage. Continuously following new styles to be homologated, led the clothing production to double, going from 50 billion pieces in 2000 to over 100 billion in 2015; at the same time, the average use of each garment decreased by 36%, with a peak of 70% in China.

A total of $ 460 billion worth of value that could be reused and instead ends up in landfills and incinerators because less than 1% of the material used in production is recycled into new clothes. As far as wholesale distribution is concerned, the problem takes a longer turn: the unsold clothes end up in outlets, then in stores like Marshalls, TJ-Max or Dress for Less, where the unsold is sent to poor countries creating considerable problems on the ‘local economy that is no longer incentivized to buy as it is found with tons of free products, ready to use that eventually end up disposed of. For this reason, many of the brand owners who are concentrating their efforts on promoting a responsible and sustainable production concept will soon be working on the aspect of managing the life ending of the products as the textile numbers are dizzying and the sector is second, due to pollution from waste disposal, only to oil.

Regardless of the social effects alone, employment in the textile sector in underdeveloped countries is often synonymous of low pay, exaggerated working hours, child labor and slavery conditions. Bangladesh, one of the poorest countries in the world, has based a large part of its economy on the export of clothing for European and North American department stores: with a value of exports of 72 billion dollars, it ranks third in the ranking after Thailand and India, defined with Bangladesh “the tailors of the world” and can be considered among the winners of the free global competition triggered by the end of the Multifibre Agreement, that regulated international trade with the quota mechanism. Bangladesh imports more than 80% of its cotton in the form of yarn. Once processed in factories it requires more than 100 different primate operations to be transformed into garment. Delays on deliveries result in a 5% deduction from buyers for each week of delay.

To show some numbers: The apparel industry looks like a $ 1.3 trillion billed business, employing more than 300 million people worldwide, and employing over 98 million tons of non-renewable resources annually, including oil to produce synthetic fibers, fertilizers for cotton plantations, chemicals to produce, dye and finish fibers and fabrics. 93 billion, instead, are the cubic meters of water that contribute to worsening drought events with the emission of about 1.2 billion tons of CO2 and 500 thousand tons of micro-plastic fibers poured into the ocean.

This being the case, the forecasts for 2050 are not encouraging: The consumption of non-renewable resources would spurt at 300 million tons and 22 million tons of micro-plastic fibers would be poured into the ocean.

For all this to end, all the people in the world must question themselves, increase their knowledge, and do something, because purchasing is the last click on the long journey that involves thousands of people: the invisible work force behind the clothes we wear.

Waste and recycling were hot topics during the Fashion Revolution because talking about recycling is one of the key points of eco-sustainable fashion and it is linked to the minimum reduction of waste because we try to reuse everything we can and throw away only the bare essentials. As the Ellen MacArthur Foundation proposes to replace the linear model with that of circular economy, our garments can have another chance thanks to the creativity that brings them back to life in new forms. There are companies, such as The Nomad Tribe, by Valeria Savino, thatdirectly reuse the garments taken from the appropriate areas or which collect them door-to-door and then cut and sew them creating jackets, dungarees and jeans in an absolutely innovative way. Unconventional garments, mostly reversible.

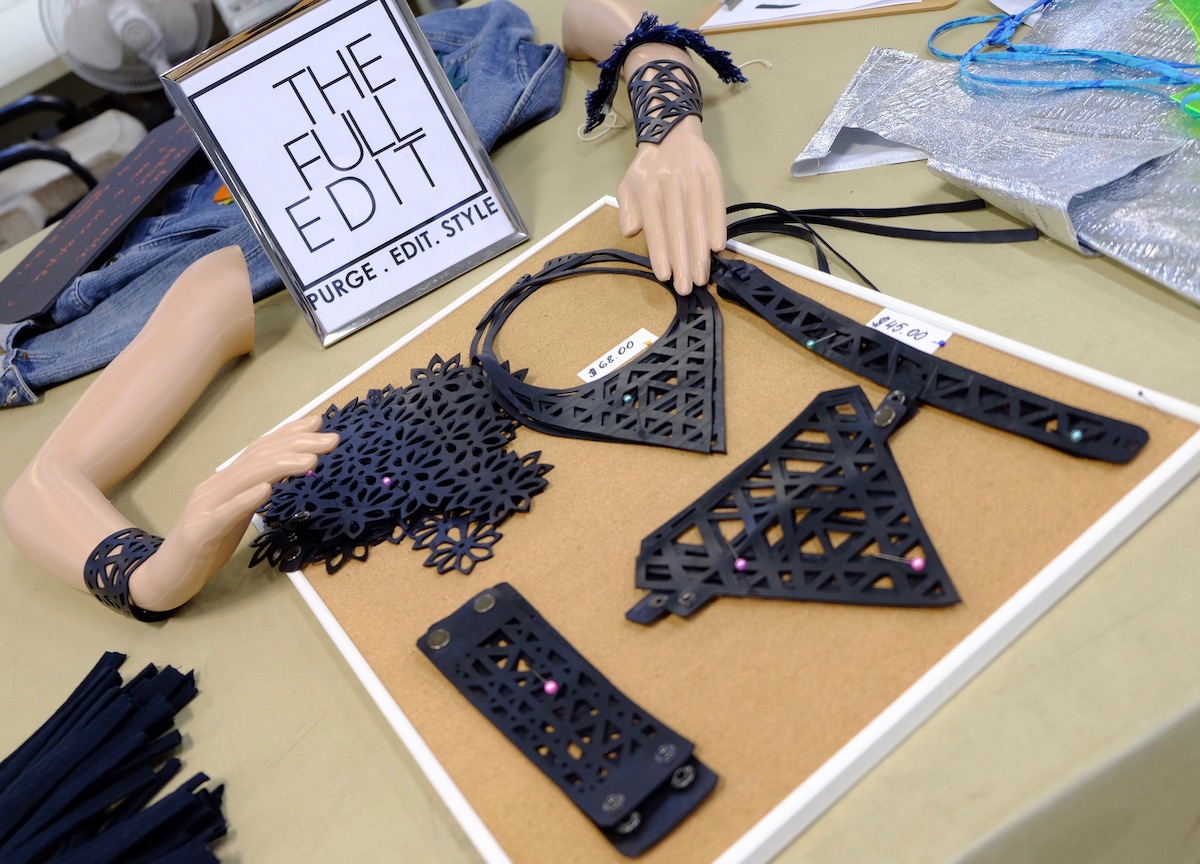

The Full Edition, a brand created in 2013 by Colleen Coughlin, after leaving Victoria Secret, uses used tires with which it makes necklaces, bracelets and semi-rigid plastic bags that become really cool tops.

Sophie Zembra selects only for her boutique brands that meet the requirements of sustainability: they are eco-friendly, come from fair trade, artisanal and social, use recycled materials and are actually made in the USA by American artisans who work in accordance with everything this is. Last but not least, that does not involve the use of animals, because animal rights are also very important, and the first step required is the replacement of animal furs followed by the replacement of other materials such as feathers or wool.

Discarded fabric strips being processed become beautiful and colorful pendants for Veronica Pesantes and her partner Jonnika, high school classmates, then co-founders of The Onikas whom purchases clothing from India to Ecuador, where skilled printers cut blocks in wood according to the drawings supplied and then use it to personalize their fabrics.

Karelle, from Krelwear claims to have a reduction of zero rejection as she personally selects the suppliers of yarns that arrive in rows at her atelier and works them as requested by the client. During the Fashion Revolution, for example, she made a top of quickie couture – clothing garment made in a very short time, usually an hour – on request, with a circular frame. As a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Karelle reuses cut-out and beautifully crafted and colorful scraps to create true large-scale works of art, such as the one displayed behind the guest discussion panel.

Carolina C. from Carolina Kleinman, on the other hand, prefers to personally meet her suppliers by doing first-round audits around the world, mainly in Mexico, Peru and India which, in addition to giving excerpts of wonderful humanity, allow our clothes to be identified with people with a name and a face.

Carolina Kleinman and Rosita in Cusco, 2006.

Starting with the use of eco-friendly fabrics, including linen and silk, many companies in recent years have started using them for their clothes. There are so many alternatives in the making of sustainable fashion, ethics, or green as you prefer: buy from artisans to promote local products and fair trade or prefer second-hand clothing, vintage and donate those that are no longer used . In this regard, within the Fashion Revolution Miami a clothing swap was set up, an exchange of clothes in which one or more items are left in good condition and the same number of items left belonging to someone else is taken, according to Patrick Duffy of the Global Fashion Exchange, this is one of the best ways to facilitate the recycling of clothing, whatever is not chosen is collected and then recycled. The global annual goal is to collect 1 million pounds. (500,000 kg) of clothing worldwide during the year and only in Miami the Fashion Revolution collected 125 pounds of clothes on Saturday.

It is time to buy clothes made in respect of the environment and workers, trying to adopt a style that transcends the current trends and favor resistant and quality fabrics, so as to decrease the pace of purchases and buy less clothes, less often, in order to save money and waste. And when you have time, tools and skills, give yourself to the dyi (do-it-yourself): get new clothes from old clothes, customize anonymous garments to make them unique.

All this fashion system is part of the definition of “circular economy” given by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which is very different from the “linear economy”. If in the linear economy the product is the source of value creation, profit margins are based on the difference between market price and production cost, to increase profits, the aim is to sell more products by lowering production costs. Circular the product is focused on the provision of a service and the competition is based on the creation of an added value of the service of a product and not only on the value of its sale. The products are part of the company’s assets and the extended responsibility of the producer guides the longevity of the product, its reuse, its reparability and its recyclability.

The stories hidden behind our clothes hide much more than we are willing to see or pay and it is only our purchasing power that can make the difference. Our way of buying less, finding for our leaders alternative creative solutions that are able to give new life to the garment recycling it in another or giving it to those who care to minimize processing waste is a viable alternative to the cause. Today we talk about a target of people with a good culture, informed and sensitized on the subject, the hope is to spread these principles to a wider audience, from fashion schools to universities, which ultimately affect the whole because of stories we tell to wear one every day with a happy ending or less.

It’s up to us to make the right choice, in the meantime, watch the Guardian video about the Rana Plaza disaster: