This post is also available in:

The PAMM inaugurated the first major retrospective of the Colombian artist Beatriz González: 150 works composed from 1960 to the present on display from April 18th to September 1st. A great artistic exhibition that sees the Pérez Art Museum of Miami as protagonist, engaged for forty-eight years (and known before 2013 as MAM: Miami Art Museum) in promoting Latin American art and architecture, reflecting the diverse communities that make it up, and promoting the exhibition and acquisition of artistic works for permanent collection. PAMM has recently purchased two other works by the artist.

Beatrix González was born in 1938 in Bucaramanga, Colombia, and lives in Bogotá. She is known as one of the founders of Modern Colombian Art and one of the most expressive post-war voices in Latin America: her rich color palette evokes her hometown and advertising images while her vernacular painting represents the traditions of Colombian culture that she skillfully combines with irony and self-awareness, throwing critical light on the notions of Colombian society’s taste, class, gender and ethnicity. She began to draw when she was still a child, but as her mentality considered art a job not on the same level with medicine or jurisprudence, she opted for architectural studies: a noble faculty but which she left after two years because it did not arouse the interest it should have.

In the meantime she became passionate about art history, especially that of the Renaissance period and that of the European art schools and, encouraged by her father’s wish to open a workshop as an advertising graphic, she enrolled in a graphic design class at the end of which, with some friends, she managed to open a study inside the university. Under the direction of Professor J. Antonio Roda, with extreme objectivity she recognizes that still lifes and painting from life are not for her and she begins to produce art by painting the great classical masters, especially Veermer and Velazquez, in a very subjective way.

Among the first works that receive the approval of her teacher are the works of the two artists she manages to abstract with skill, among them: Encajera Almanaque Pielroja (1964), inspired by the painting The Lacemaker, by Veermer, and the work of Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda, of which it reproduces a version of the detail in La Redencion de Breda, (1962) and following which, she is invited to preside over the chair of Art History at the Architecture faculty. Chair that she refuses to be able to completely dedicate herself to art.

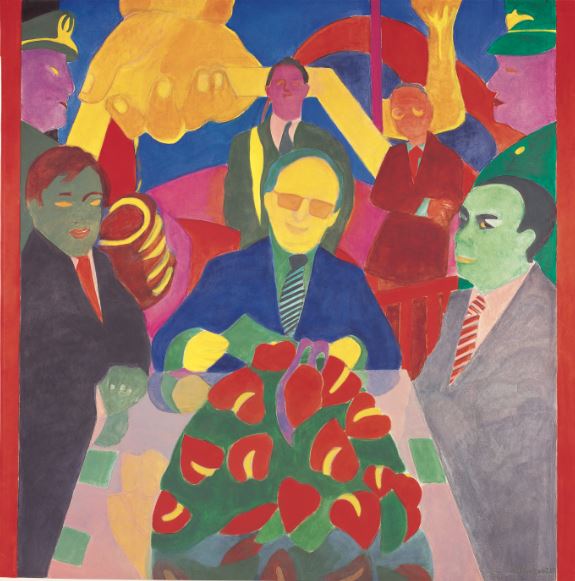

Over time, she will not disdain even Renoir of which she composes a work on sale by the centimeter (10 metros de Renoir, 1977) and Manet, with which she begins a period of composition on large formats which she inaugurates with the work Telon de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza, composed for the Venice Biennale in 1978 on two large canvases, and based on Le déjouner sur l’herbe de Manet. Goya also exercised a certain fascination with Beatrix González, not so much for the painting itself, but rather for the role of court painter to which she was inspired for her concept of cortina art as she calls it, in the representation of works policies, cared for in titles with shrewd irony. Among her favorite subjects she portrays the twenty-fifth Colombian president Julio Cesar Turbay Aiala, whose vanity in being immortalized by the camera enables her to copy some images of the president and his followers in a climate of total falsity. It is a photograph taken during a party of the president to arouse the interest of Beatrix who reproduces in her own way with a lithograph, on a curtain thinking that in the end the process was not very different compared to the previous reproduction on furniture. Among the other presidents she portrays Carlos Lleras Restrepo and Belisario Betancourt (Sr. Presidete qué honor estar con usted en este momento historico, 1986, and Los papayagos ) with which she opens a Pandora’s box denouncing the problems related to drug trafficking, Colombian political corruption and the attack of the revolutionary insurrectionary guerrilla organization of the left called Movimento 19 (M19).

In the 1970s she began to work on low-cost furniture when she came across accompanying her husband from the junk shop. The works on the furniture are essentially composed of metal plates painted with enamel with images that refer to the great classics of art, among them first of all the Naturaleza casi muerta (1970) and Gratia Plena (tocador), of 1971 in foil made of steel with enamel and decorative elements reminiscent of wood: A mere reproduction of low-quality western products that represent the farce of the Colombian society put in place on the basis of what it shows off having and not for what it really is has.

She also began to work on screenprint on paper for typical images to denounce the Colombian bourgeois class in which the family nucleus posed dressed in black proud of having two nuns and a soldier in the family (Ya llegó la sceccia II, 1979).

Abstract painting is a theme dear to Beatriz González who shares it with what Fernando Botero’s works are in those years, who will confess to having been his inspiration in artistic Colombia in the shadow of Western art, and of which she says: “He was the magician to whom to adapt the pastel”.

The art of González diversified from that of Botero when his glorious moment arrived which led her to reproduce in a very personal way the image of a small photograph (5×5 inches), in which a man and a woman appear smiling woman with a bouquet of flowers: Los Suicidios del Sisga, from 1965, her most famous work, then reproduced in different variations. The photograph was taken on commission by the two young farmers before committing suicide to declare the purity of their pristine love. A very sad story through which the art of Beatriz González takes flight in the Colombian art scene and which helps her to focus on the idea of wanting to represent works related to death and misfortune, which, however, connotes, almost in antithesis with the theme, very bright colors.

Extremely vivid colors, with bold combinations typical of the graphic and spread with flat backgrounds in which it is the same color that gives the subjects corporeality. The idea of flat backgrounds was born in the artist following the analysis of the images of the newspaper (the Bucaramanga magazine and the Life magazine, a Latin American edition) of poor graphic quality, which crops, preserves and copies with precision on different scales, and from the vision of the Sagrada Familia by Antoni Gaudì in Barcelona: a very complex architectural work that results however in the homogeneously yellow whole. In the 1970s Beatrix González composed works inspired by the royals of England, La reina Isabel se pass por el puente de Boyacá (1968) and La actualidad ilustrada (1973).

The critics will later define pop works by pointing to Beatrix Gonzalez as the first Colombian pop artist, a label that she will reject saying she never felt like an artist, indicating colors as a simple homage to her city of birth, Bucaramanga combined with the desire for originality . In temporal terms, moreover, Beatrix González has known the works of some artists of the Pop Art, among which Indiana, Rosenquist and Oldenburg, only after a trip to Holland happened a posteriori.

The art of the Colombian artist undergoes a strong turn with flat backgrounds of dark and dark colors after the years of the Colombian Violencia: a brutal period characterized by strong clashes between supporters of the Liberal Party and those of the Conservative Party as a result of which they died over 200,000 people. Beatrix González actively participated in the cause in the 1980s, denouncing issues of a social nature that refer to years of corruption, political fragmentation and violence with an even wider social scope than the Colombian drama, which comes to encompass problems related to the destruction of the indigenous village of Wiwa, internally displaced persons and refugees from Venezuela. Years of abuse and violence portrayed with human features of unarmed bodies covered with handkerchiefs (Los Predicadores, 2000) or flowing along the river (La corriete, 1992). Images that, as in a film by Michelangelo Antonioni, run small, dwelling on the faces of the people who cover their eyes (La delicia 12 and La delicia 14), on the faces of mothers who have been kidnapped by their children (Sin titulo) or on her that naked (the intellectual honesty in reporting the events) gets her hands to her desperate head (Autorretrato desnuda llorando, 1997).

The greatest work of Beatriz González is the work of art composed in 2009 when one evening the moonlight highlighted the niches of the Central Cemetery of Bogotà, abandoned in 2005 and composed of six neoclassical buildings, for a total of 9857 niches, in which in a time the dead were put. The buildings are now the subject of discussion for the approval of a project that provides for their demolition in favor of a soccer field. In addition to recalling the dead for La Violencia Colombiana, Beatrix wanted to raise public awareness in favor of their maintenance and with the help of her student Doris Salcedo, she covered each niche with one of the eight different screenprint composed in charcoal, in which appear black silhouettes of people carrying corpses around a stick carried on the shoulder of the holy field during the riots.

The exhibition also includes more recent works inspired by the lighter personal problems including Duelo with cellular, from 2018: a clear reference to the use of digital.

After having had the opportunity to preview the well-distributed exhibition with absolute calm, in which it is possible to make an excursus both on the mediums and on the different techniques used during the sixty years of Beatrix González’s activity, visitors participated in the the meeting was attended by the 81-year-old artist, the curator of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston who is also Wortham Curator of Latin American Art and Director of International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the MFA Houston and the chief curator of the PAMM, Tobias Ostrader, who interviewed the jovial artist in a very familiar way focusing on the focal points and passages that marked the stages of his career, delighting guests. Another big step for the PAMM Museum that its director Franklyn Sirmans thanked Jorge Perez, who was present at the event and all the guests who helped support the exhibition with contributions and donations.

And for the question concerning how much pictorial art can be in danger in a digital world, Beatrix González replies that every era has a cycle and not even photography has managed to eradicate lithography, in the same way art will be continuously subject a stimulus on which to work to renew culture.

.